Is It Wrong to Eat Your Dog Haidt and Dias Analysis Review Summary

Abstract

A central question in the written report of moral psychology is how immediate intuition interacts with more thoughtful deliberation in the generation of moral judgments. The present study sheds additional light on this question by comparison adults' judgments of moral permissibility with their judgments of physical possibility—a form of judgment that as well involves the coordination of intuition and deliberation (Shtulman, Cerebral Development 24:293–309, 2009). Participants (Due north = 146) were asked to guess the permissibility of 16 extraordinary deportment (e.g., Is it ever morally permissible for an eighty-year-former woman to have sex with a 20-twelvemonth-quondam man?) and the possibility of 16 extraordinary events (e.g., Will it ever be physically possible for humans to bring an extinct species dorsum to life?). Their trend to judge the extraordinary events as possible was predictive of their tendency to guess the extraordinary deportment as permissible, fifty-fifty when controlling for disgust sensitivity. Moreover, participants' justification and response latency patterns were correlated beyond domains. Taken together, these findings propose that modal judgment and moral judgment may exist linked by a common inference strategy, with some individuals focusing on why deportment/events that do non occur cannot occur, and others focusing on how those same actions/events could occur.

The field of moral psychology has undergone a renaissance in recent years, spurred largely by Haidt'south (2001) social-intuitionist model of moral judgment. Co-ordinate to this model, moral judgments are not the product of slow and deliberate reasoning, as had been emphasized in earlier models of moral cognition (Kohlberg, 1981), but the product of fast and automatic intuitions. Explicit reasoning, if it occurs at all, takes the class of post-hoc rationalization, with verbal justifications for moral judgments constituting a result, not a cause, of the judgments themselves. Support for this model has come from a growing body of studies demonstrating the primacy of bear upon and intuition. In one such report, Haidt, Koller, and Dias (1993) asked people of varying ages, cultures, and socioeconomic backgrounds to approximate the permissibility of harmless, notwithstanding offensive, deportment, like cleaning one's toilet with the national flag or eating one'southward dog subsequently it had been killed in an accident. They institute not only that participants' judgments were predicted by their melancholia reactions, but also that affect was a stronger predictor than appraisals of harm in seven of the 12 subsamples, with virtually participants denying the permissibility of any action accounted disgusting or disrespectful, regardless of its effect on interpersonal well-being.

These findings, among others (e.one thousand., Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley, & Cohen, 2001; Wheatley & Haidt, 2005), have been taken as evidence that the before, Kohlbergian focus on reason and reflection was misguided. Notwithstanding, the move from rational models of moral judgment to intuitionist models has seemingly come full circle, with many scholars arguing that intuition lonely cannot account for the total range of moral judgments. Lombrozo (2009), for instance, has shown that 1's explicit endorsement of a consequentialist philosophy predicts one's stance toward moral dilemmas that pit consequentialist principles against deontological principles, such as the "Trolley trouble." Cushman, Young, and Hauser (2006) showed that, in judging the permissibility of harmful actions, almost adults are consciously aware of at least two moral principles—impairment caused past action is worse than harm caused past inaction, and harm acquired by physical contact is worse than harm caused at a distance—and their judgments appear to honor those principles. And Zalla, Barlassina, Buon, and Leboyer (2011) accept shown that the ability to distinguish harmful actions from harmless, still offensive, actions is mediated by the power to appraise intentional action and discern the welfare of others.

While these studies advise a role for explicit, deliberate reasoning in moral judgment, they have focused on such processes inside the context of the moral judgments themselves. That is, their measures of explicit reasoning are not wholly contained of the judgments that they purport to explain. One notable exception is a recent study by Cushman and Young (2011), comparing how individuals evaluate events involving merchandise-offs in man lives with how they evaluate structurally analogous, but nonmoral, events involving trade-offs in cloth outcomes. Cushman and Young showed that moral judgments runway both causal attribution (i.east., attributions of whether or not the protagonist caused the events to transpire) and intentional attribution (i.e., attributions of whether or not the protagonist intended the events to transpire). Simply are causal and intentional attribution the only forms of nonmoral cognition tracked by moral judgments? Might there exist other forms further downstream, after causality and intentionality have been assessed? In the present report, we explored this possibility by comparing participants' moral judgments to their judgments in a conceptually distinct, yet logically related, domain: physical possibility. Our rationale for making a comparing between the moral and modal domains was threefold.

Get-go, modal judgment appears to share many of the same computational demands equally moral judgment. But as violations of social norms (e.g., eating i's dog) ofttimes arm-twist immediate intuitions ("that's not OK!") that may be modified or rejected on the basis of further reflection ("well, if the dog is already dead . . ."; Greene & Haidt, 2002), violations of empirical regularities announced to produce a similar chain of reasoning (Shtulman, 2009). For instance, hypothetical events, like living for 200 years or traveling beyond the Milky Way, likely elicit the firsthand intuition that such events are impossible, given that neither has occurred nor is likely to occur anytime soon. But farther deliberation—for instance, deliberations about genetics and medicine, in the case of man longevity, or deliberations about spacecrafts and wormholes, in the case of extraterrestrial travel—may ultimately pb to the decision that such events are possible. In this manner, both modal judgment and moral judgment appear to crave the coordination of immediate intuition, derived through automatic semantic or episodic associations, and more considered reflection in light of one's (explicitly known) empirical and theoretical commitments. In that location is, however, one meaning difference between the 2 forms of judgment, which is that only moral judgment appears to be grounded in emotion every bit well. Indeed, psychologists have identified a number of emotions that seem to exist specifically "moral" in nature, including guilt, shame, gratitude, and contempt (Haidt, 2003). While there has been no documentation, to our noesis, of a corresponding suite of "modal emotions," such emotions, if they do exist, would seem to play a less significant role in modal judgment than the role played by emotion in moral judgment (Russell & Giner-Sorolla, 2011; Strohminger, Lewis, & Meyer, 2011). Thus, mutual patterns of reasoning beyond the two domains might aid determine the proportion of variance in moral judgment that tin exist accounted for by seemingly nonaffective processes.

Second, consistent with the computational similarities outlined in a higher place, the modal and moral domains share linguistic similarities too. About all languages brand a lexical stardom between factual claims, expressed with auxiliary verbs similar "is" and "does," and modal claims, expressed with auxiliary verbs like "could" and "should" (Boyd & Thorne, 1969; Perkins, 1983). Whereas factive auxiliaries are used to express assertions of truth, modal auxiliaries are used to express assertions of possibility or permissibility. The validity of such assertions cannot be evaluated empirically, only must instead be evaluated against a fix of preexisting commitments or principles. The claim "information technology could rain," for instance, is non a claim almost current weather weather condition, verifiable past direct observation, just a merits about the possibility of rain, given certain preconditions (due east.g., cloudy skies). Philosophers have long noted logical relations betwixt alethic modality, or the domain of possibility and necessity, and deontic modality, or the domain of permissibility and obligation (see Hughes & Cresswell, 1968), simply the psychological relations amid these domains have not been well studied.

Tertiary, psychologists take documented similar developmental trajectories in the modal and moral domains. Specifically, researchers have institute that young children have a more parochial sense of both what is possible and what is permissible than do older children and adults. In the modal domain, young children are less likely than older children to assert the possibility of events that violate empirical regularities just not concrete laws, similar communicable a fly with chopsticks or finding an alligator under the bed (Shtulman, 2009; Shtulman & Carey, 2007). In the moral domain, immature children are too less probable than older children to affirm the permissibility of actions that violate social conventions but non moral prescriptions, like singing "Jingle Bells" at a birthday political party or wearing pajamas to school (Browne & Woolley, 2004; Kalish, 1998; Komatsu & Galotti, 1986). Both differences accept tentatively been explained in terms of children's developing sensitivity to the limitations of their own experiences and intuitions. That is, children initially announced to estimate anything that defies expectation every bit impossible or impermissible, but gradually come to reflect on the validity of those intuitions prior to passing judgment (run into Shtulman, 2009; Woolley & Ghossainy, in press). It remains an open up question, however, whether commonalities in modal development and moral developmental arise from a common source—for case, a shared inference strategy—or are merely coincidental.

In short, there are both theoretical and empirical reasons for comparing moral judgment to modal judgment, the most important being that shared variance across the two domains might indicate a common form of reasoning. Nosotros undertook this comparison by eliciting judgments and justifications for events that are empirically infrequent (or nonexistent) but do non violate whatsoever commonly known physical laws or moral prescriptions. Our prediction was that individuals who were open up to the possibility of many extraordinary events would also be open to the permissibility of many boggling actions and would justify their judgments differently than those who were more skeptical across the board.

Method

Participants

The participants were 146 college undergraduates recruited from introductory psychology courses in substitution for extra credit. 1 additional participant was tested but excluded from the final analyses on account of answering all questions "aye" (a statistically deviant response pattern).

Process

The participants were presented sixteen yes-or-no questions about physical possibility and 16 yes-or-no questions about moral permissibility in MediaLab v1.21. Their response latencies were recorded, although participants were not explicitly apprised of the fact that judgments were being timed. The number of characters in each question varied minimally, from xc to 99, and the ordering of the 32 questions was randomized across participants in gild to control for do furnishings. Response latencies more two standard deviations from the hateful were removed from the data set (iii.6 % in full).

All questions about physical possibility took the form "Volition information technology ever be physically possible for humans to [event]?" and all questions about moral permissibility took the form "Is it always morally permissible for [actor] to [action]?" The boggling actions, which are listed in Table one in decreasing club of perceived permissibility, were intended to be potentially but not patently immoral (i.e., prohibited by harm norms), like spitting in one'southward glass earlier taking a drink or replacing a borrowed necklace with an identical copy. Half were taken from previous studies involving offensive, yet harmless, actions (Haidt, McCauley, & Rozin, 1994; Haidt et al., 1993; Nichols, 2002), and one-half were created from scratch. The extraordinary events, which are listed in Table 2 in decreasing society of perceived possibility, were intended to be potentially but not manifestly incommunicable (i.due east., prohibited past physical laws), similar resuscitating a person frozen for many years or teleporting an object to a afar location. Some were taken from previous research on modal judgment (Shtulman, 2009; Shtulman & Carey, 2007), simply about were created from scratch. All items were pretested with an undergraduate sample to ensure that they elicited variable judgments.

It bears mentioning that a scattering of the items in each domain did not conform to these criteria. Rather, they were selected to be unambiguously possible (eastward.chiliad., powering a car exclusively with solar energy), unambiguously permissible (e.k., attending form in one's pajamas), unambiguously impossible (e.yard., catching and holding a shadow), and unambiguously impermissible (due east.thou., killing one'south wife to collect her life insurance), and so every bit to prevent participants from adopting a "yes" bias or a "no" bias. Even so, participants' judgments varied even on these "control" items, and then they were included in the last analyses as well.

Following the modal/moral judgment job, participants were administered two instruments that accept been shown to be predictive of moral judgment in prior inquiry: Haidt et al.'s (1994) Disgust Scale (see Nichols, 2002; Wheatley & Haidt, 2005), and Cacioppo and Petty's (1982) Need for Cognition Scale (see Bartels, 2008). Our purpose in administering these instruments was to make up one's mind whether the predictor variable of interest—participants' modal judgments—could explain some of the variance in their moral judgments beyond that explained past these instruments alone. The ordering of the instruments was randomized across participants, as was the ordering of their items.

Coding

In addition to making yes-or-no judgments, participants also justified their judgments, generating a full of 4,672 justifications (one justification per each of 32 judgments for 146 participants). These justifications were sorted into i of 3 categories: conditional, principled, or redundant. Conditional justifications referenced specific circumstances under which the target item would (or would not) be possible or permissible. Principled justifications referenced full general principles of a physical or social nature that the target item either violated or satisfied. Finally, redundant justifications elaborated on, just did non actually justify, the judgment in question.

To illustrate, consider the following justifications for why it is morally permissible for an 80-year-old adult female to have sex with a 20-year-quondam man: "Both parties are of legal age" and "sex is a individual affair" were coded equally principled; "if they love each other" and "if they both consent" were coded as conditional; and "it's disturbing but not immoral" and "socially weird but morally fine" were coded as redundant. Also, consider the following justifications for why information technology is physically possible for humans to perform a successful brain transplant: "The brain is just one of many organs" and "It is a unproblematic physical relocation" were coded as principled; "if we develop the right kind of life back up" and "if information technology weren't rejected by the recipient" were coded as conditional; and "given enough time anything is possible" and "I don't see why not" were coded as redundant.

Importantly, all three categories could be applied to justifications in both domains (modal and moral) and for both types of judgment (affirmative and negative). 2 trained coders applied the coding scheme to all 4,672 justifications independently. The overall agreement was 84 % (Cohen's kappa = .76), and disagreements were resolved by a tertiary coder. In total, 47 % of justifications were coded as conditional, 38 % as principled, and 15 % every bit redundant.

Results

Judgment patterns

As predictable, participants varied in both the number of events judged possible (range = 2 to 15, Grand = 7.3, SD = 3.0) and the number of deportment judged permissible (range = 2 to 16, Grand = 9.8, SD = 3.0). The former comprised participants' modal judgment score, and the latter their moral judgment score. Pearson's correlations revealed that moral judgment scores were positively correlated with modal judgment scores (r = .34, p < .001), negatively correlated with Disgust Scale (DS) scores (r = −.45, p < .001), and uncorrelated with Demand for Noesis Scale (NCS) scores (r = .xi, north.s.).

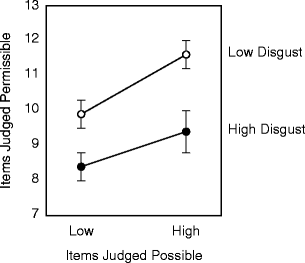

To determine whether the furnishings of modal judgment and disgust sensitivity were additive or interactive, we sorted participants into four groups on the ground of whether their modal judgment score was higher up or below the median score of 7 (on a scale from 0 to 16) and whether their DS score was to a higher place or below the median score of 2.0 (on a scale from 1.0 to 3.0). The moral judgment scores for these 4 groups are displayed in Fig. 1. A repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed significant main effects of both modal judgment [F(1, 142) = 7.58, p < .01] and disgust sensitivity [F(1, 142) = fourteen.85, p < .001], but no interaction between them [F(i, 142) < 1], indicating that modal judgment predicted moral judgment at both loftier and low levels of disgust sensitivity. Consequent with this assay, we found that the correlation between modal judgment scores and moral judgment scores in the full sample remained significant, fifty-fifty after decision-making for DS scores (partial r = .22, p < .01).

Mean numbers of boggling actions judged equally permissible (± SE) as a function of (a) disgust sensitivity and (b) the disposition to judge extraordinary events as possible

I additional assay was conducted to explore the possibility that the effects documented in Fig. one were driven by a distinct subset of the moral items. These items were, later on all, quite diverse, ranging from violations of authority (e.g., using an American flag as a rag) to violations of purity (east.g., masturbating with a dead chicken) to violations of sacred values (due east.chiliad., committing suicide out of boredom). Relations between moral judgments and the three predictor variables—modal judgment scores, DS scores, and NCS scores—were thus analyzed separately for each item, as is shown in Table 3. These correlations were point-biserial, given that responses to each item were dichotomous ("yep" vs. "no"), which rendered them potentially more volatile than the Pearson'southward correlations noted above. That said, the correlations between moral judgments and modal judgments were consistently positive, with eight (out of 16) reaching statistical significance, and the correlations between moral judgments and DS scores were consistently negative, with 11 reaching statistical significance. The correlations betwixt moral judgments and NCS scores, on the other hand, hovered near naught, with none reaching statistical significance. Thus, the effects at hand exercise not appear to be restricted to ane, and only ane, category of moral consideration, although hereafter enquiry will be needed to make up one's mind whether some categories of moral consideration are more strongly associated with modal judgments than are others.

Justification patterns

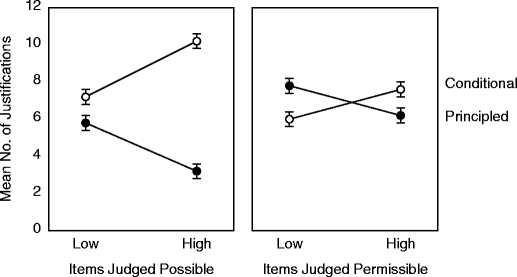

Justifications for modal and moral judgments were correlated beyond domains in two ways. Beginning, they were correlated in terms of frequency: The more oft that participants provided a item blazon of justification in one domain, the more than oftentimes they provided the same blazon of justification in the other domain (for conditional, r = .29, p < .001; for principled, r = .29, p < .001; for redundant, r = .44, p < .001). 2d, the justifications were correlated in terms of role: The more than often participants made either affirmative ("yes") or negative ("no") judgments, the more ofttimes they provided particular types of justifications. Specifically, provisional justifications were positively correlated with affirmative judgments in both domains (modal domain, r = .59, p < .001; moral domain, r = .48, p < .001), and principled justifications were positively correlated with negative judgments in both domains (modal domain, r = .51, p < .001; moral domain, r = .36, p < .001). In other words, the more than often that participants judged items as possible or permissible, the more oftentimes they provided conditional justifications for those judgments, and the more often that participants judged items every bit impossible or impermissible, the more often they provided principled justifications for those judgments. Redundant justifications were non significantly correlated with either type of judgment.

These effects can be seen in Fig. 2, which depicts the frequencies of conditional and principled justifications as a function of modal and moral judgment scores (where "low" corresponds to a below-median, and "loftier" to an above-median, number of affirmative judgments). Although the overall frequencies of each justification type differ by domain, the interactions betwixt justification type and judgment score are like across domains. A pair of repeated measures ANOVAs, in which Justification Type (conditional vs. principled) was treated equally a within-participants factor and Judgment Score (depression vs. loftier) was treated every bit a between-participants gene, confirmed that the interaction between justification type and judgment score was significant in both the modal domain [F(1, 144) = 135.51, p < .001] and the moral domain [F(i, 144) = 12.84, p < .001]. Thus, participants who were disposed to provide different types of judgments also appeared to be disposed to provide different types of justification.

Mean numbers of principled and conditional justifications provided in each domain (left, items judged possible; right, items judged permissible) (± SE) as a function of the disposition to gauge items in that domain every bit possible or permissible

1 concern with this estimation is that certain judgments may lend themselves better to certain types of justification. In item, affirmative judgments may be easier to justify by a condition than by a principle, and negative judgments may exist easier to justify by a principle than by a condition. To rule out this possibility, we separated the justifications provided for affirmative judgments from those provided for negative judgments and reran the ANOVAs described above. These analyses revealed pregnant interactions between justification type and judgment score, fifty-fifty for judgments of the same blazon [modal domain and affirmative judgments, F(ane, 144) = xiii.94, p < .001; modal domain and negative judgments, F(1, 144) = 12.43, p < .001; moral domain and affirmative judgments, F(1, 144) = 81.65, p < .001; moral domain and negative judgments, F(1, 144) = 48.54, p < .001]. The interactions displayed in Fig. 2 do non, therefore, merely reflect a coincidental association between certain types of judgments and sure types of justifications.

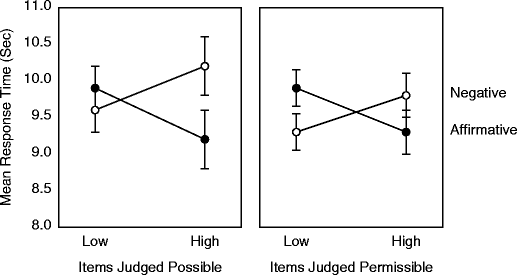

Response latency patterns

On average, participants took 9.4 south to brand their modal judgments (SD = 5.two) and 9.iv southward to make their moral judgments (SD = 5.ane), and in that location was no relation between the blazon of judgment made (affirmative vs. negative) and the speed of that judgment in either domain. However, an interaction was observed between judgment type and judgment score, as is shown in Fig. three: Participants with "low" judgment scores took longer to make affirmative than to make negative judgments, and participants with "high" judgment scores took longer to brand negative than to make affirmative judgments. The statistical reliability of these interactions was confirmed with repeated measures ANOVAs in which Judgment Type (affirmative vs. negative) was treated as a within-participants gene and Judgment Score (low vs. high) was treated every bit a between-participants cistron [modal domain, F(1, 144) = 6.54, p < .05; moral domain, F(i, 144) = 4.33, p < .05]. Generating judgments that ran counter to one's typical judgment pattern thus appeared to take additional cognitive endeavour, regardless of whether that pattern was to judge items as predominantly possible/permissible or to gauge them as predominantly impossible/impermissible.

Mean response times for affirmative and negative judgments in each domain (left, items judged possible; right, items judged permissible) (± SE) as a function of the disposition to judge items in that domain as possible or permissible

Discussion

Assertions of possibility and permissibility overlap in their linguistic expressions (Perkins, 1983) and logical forms (Hughes & Cresswell, 1968), but exercise they also overlap in any genuine psychological respects? Our findings suggest that they practice. Using extraordinary events to arm-twist modal judgments and extraordinary actions to arm-twist moral judgments, we found that the more often that participants judged the extraordinary events as possible, the more than often they judged the extraordinary actions every bit permissible, irrespective of their cloy sensitivity. Moreover, judgments in both domains were predicted by similar patterns of justification and like patterns of response latencies. That is, the disposition to judge the items at hand as possible or permissible was associated with (a) an increased provision of conditional justifications, (b) a decreased provision of principled justifications, and (c) longer response times for the judgments of impossibility or impermissibility. In contrast, the disposition to judge those same items as incommunicable or impermissible was associated with (a) an increased provision of principled justifications, (b) a decreased provision of conditional justifications, and (c) longer response times for judgments of possibility or permissibility.

To provide more than of a season for these findings, consider the difference betwixt Participant 48, who judged 75 % of the modal items as possible and 81 % of the moral items equally permissible, and Participant 141, who judged merely 38 % of the modal items as possible and only 13 % of the moral items equally permissible. For the event of traveling at the speed of lite, Participant 48 claimed this consequence was possible, justifying it with the conditional justification "the pull a fast one on is to find a fuel source that can go us to that speed and maintain it for long travels," whereas Participant 141 claimed that this outcome was impossible, justifying information technology with the principled justification "the human body cannot handle the speed." For the action of using a sterile flyswatter as a cooking utensil, Participant 48 claimed that this issue was permissible, justifying it with the conditional justification "every bit long as he hadn't killed any flies with it," whereas Participant 141 claimed this upshot was impermissible, justifying it with the principled justification "its function is but to hitting flies." In the seven instances that Participant 48 judged an item to be impossible or impermissible, she took an average of 4.4 s longer to do then, and in the 8 instances that Participant 141 judged an particular to be possible or permissible, she took an average of 5.7 southward longer to do then.

Equally a whole, these findings suggest that modal judgment and moral judgment may exist linked by differences in one's overall approach to the evaluation of nonfactual claims. While some individuals appear to focus on why certain events and actions that practise non occur cannot occur, others appear to focus on how those aforementioned actions and event could occur. Whereas the onetime grouping tend to place general principles that would preclude the events' possibility or undermine the deportment' permissibility, the latter tend to identify specific conditions that would facilitate the events' possibility or justify the actions' permissibility. This interpretation of the data not only makes sense of the close correspondence between modal judgments and moral judgments (Fig. 1), only also makes sense of the divergence in justification patterns (Fig. 2) and response latency patterns (Fig. 3) between those with high modal/moral judgment scores and those with low modal/moral judgment scores.

Of course, given that our methods were correlational in nature, nosotros must acknowledge the possibility that the observed correlations may have been mediated past a 3rd, all the same-to-be-determined variable. "Need for knowledge" does not seem to be that variable, given its lack of association with participants' moral judgment scores, yet other possibilities include openness to experience (McCrae & Costa, 1987), cerebral reflectiveness (Frederick, 2005), or open-mindedness (Kruglanski, 2004). Certainly, the human action of accepting boggling events as possible and extraordinary actions equally permissible would seem to require degrees of both open-mindedness and cognitive reflection, only it remains an empirical question whether the relation between moral judgment and modal judgment can exist fully explained by such variables. The mere ascertainment that modal judgment and moral judgment share similar computational demands, as described above, suggests that these two forms of judgment should track ane some other more than closely than either should track a conceptually distinct ability or disposition.

Some other possible mediator of the relation between modal judgment and moral judgment is one's behavior about "natural order" or "divine will" (Brandt & Reyna, 2011; Morewedge & Articulate, 2008). Such behavior might lead one to deny both the possibility of extraordinary events and the permissibility of extraordinary actions considering those things would appear to exist forbidden by God (or some other form of supernatural bureau). In other words, participants who made mostly "no" judgments may accept been motivated by the explicit belief that, if God had intended such things to occur, and so they would occur, regularly and without question. While the data at hand cannot rule out this explanation, there are at least two reasons to doubt it. First, participants rarely appealed to religious considerations in their justifications; simply ten justifications out of 4,672 referenced whatsoever overt religious content. Second, information technology is unclear how differences in religious belief could explain the full range of findings documented hither. That is, if participants who made mostly "no" judgments did so on the basis of religious considerations, what considerations might have guided those who made mostly "yes" judgments? And why did those considerations yield opposite patterns of justification and response latency, as opposed to no pattern whatsoever? Such details imply that "aye" judgments were based on something more noun than the mere absence of religious belief.

Alternative explanations bated, the bones finding that questions almost physical possibility and moral permissibility yield like patterns of judgment, justification, and response latency has potentially important implications for the study of both forms of cognition. With respect to modal cognition, our findings imply that differences in modal judgment do not necessarily reduce to differences in knowledge or experience. The participants in our written report came from a rather homogeneous population in terms of modality-relevant knowledge (i.e., bones principles of science), yet they drew vastly different modal inferences. No 2 participants produced the same pattern of judgments, and the difference betwixt participants could be equally large as 81 %. The implication is that individuals with similar types of knowledge or experience may still course different modal judgments, equally determined by how they coordinate that cognition with their intuition (encounter besides Nichols, 2006; Weisberg & Sobel, 2012). That said, nosotros did not explicitly measure participants' concrete or biological cognition, so additional studies volition be needed to verify that differences in content cognition are non sufficient to explicate differences in modal judgments.

With regard to moral cognition, our findings imply that differences in moral judgments exercise not necessarily reduce to differences in intuition, particularly affective intuition. Participants with similar melancholia responses to the items on the Cloy Scale still varied in their moral judgments, and a significant portion of that variance was accounted for by their judgment patterns in the structurally similar, still less affectively charged, modal domain. These findings resonate with a growing body of research demonstrating that melancholia intuition is not the only component of moral judgment (e.1000., Huebner, Dwyer, & Hauser, 2009; Nichols & Mallon, 2006; Pizzaro & Bloom, 2003). Explicit reasoning may play an important office likewise, particularly in situations in which ane's firsthand intuition would announced to confute a more principled gear up of commitments and beliefs. Of course, further research will be needed to determine whether the patterns of reasoning tapped by the modal judgment task are truly explicit in nature. Manipulating the time constraints under which participants make their judgments would exist one fashion to investigate this claim, as the relation between modal judgment and moral judgment should weaken if deliberate reasoning is precluded. Some other possibility would exist to manipulate participants' melancholia states, in terms of either their general mood (à la Valdesolo & DeSteno, 2006) or their feelings of disgust in particular (à la Rottman & Kelemen, 2012), and to assess whether the relation betwixt modal judgment and moral judgment is weaker under these conditions, as well.

Perhaps the most important contribution of this research is the introduction of a new ways of comparing for analyzing the form and function of moral judgment. To engagement, moral judgment has been studied most extensively in the context of the "trolley problem" (e.one thousand., Bartels, 2008; Cushman et al., 2006; Greene et al., 2001; Lombrozo, 2009; Moore, Clark, & Kane, 2008; Paxton, Ungar & Greene 2012; Pellizzoni, Siegal, & Surian, 2010; Suter & Hertwig, 2011), all the same the tension tapped past this problem— the tension betwixt deontic and commonsensical modes of determination making—is conspicuously not the but issue of interest to moral psychologists. It would thus be ideal to identify measures of moral cognition that can be applied to other forms of moral judgment, including judgments about lying (e.thou., Perkins & Turiel, 2007), judgments nigh punishment (e.g., Descioli & Kurzban, 2009), and judgments about fairness (e.g., Stephen & Pham, 2008). Patterns of modal judgment and modal justification may provide such a measure. Not only are they empirically tractable, merely they also help farther the goal of connecting moral judgment to human noesis more than generally, such that moral judgment is studied not as a unique type of judgment, independent of all others, merely as 1 of many types requiring the coordination of prior commitments and current intuitions.

References

-

Bartels, D. M. (2008). Principled moral sentiment and the flexibility of moral judgment and decision making. Cognition, 108, 381–417.

-

Boyd, J., & Thorne, J. P. (1969). The semantics of modal verbs. Periodical of Linguistics, 5, 57–74.

-

Brandt, 1000. J., & Reyna, C. (2011). The chain of being: A hierarchy of morality. Perspectives on Psychological Scientific discipline, 6, 428–446.

-

Browne, C. A., & Woolley, J. D. (2004). Preschoolers' magical explanations for violations of physical, social, and mental laws. Journal of Cognition and Development, v, 239–260.

-

Cacioppo, J. T., & Petty, R. East. (1982). The demand for noesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42, 116–131.

-

Cushman, F., & Young, L. (2011). Patterns of moral judgment derive from non-moral psychological representations. Cognitive Science, 35, 1052–1075.

-

Cushman, F., Immature, Fifty., & Hauser, 1000. (2006). The role of conscious reasoning and intuition in moral judgment: Testing three principles of impairment. Psychological Science, 17, 1082–1089.

-

DeScioli, P., & Kurzban, R. (2009). Mysteries of morality. Cognition, 112, 281–299.

-

Frederick, Southward. (2005). Cognitive reflection and decision making. Periodical of Economic Perspectives, 19, 25–42.

-

Greene, J., & Haidt, J. (2002). How (and where) does moral judgment work? Trends in Cerebral Sciences, six, 517–523. doi:ten.1016/S1364-6613(02)02011-9

-

Greene, J. D., Sommerville, R. B., Nystrom, Fifty. E., Darley, J. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral judgment. Science, 293, 2105–2108. doi:10.1126/scientific discipline.1062872

-

Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional domestic dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 108, 814–834.

-

Haidt, J. (2003). The moral emotions. In R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer, & H. H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of melancholia sciences (pp. 852–870). Oxford, United kingdom: Oxford University Printing.

-

Haidt, J., Koller, South., & Dias, Chiliad. G. (1993). Bear on, civilisation, and morality, or Is information technology wrong to consume your dog? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 613–628.

-

Haidt, J., McCauley, C., & Rozin, P. (1994). Individual differences in sensitivity to disgust: A scale sampling seven domains of disgust elicitors. Personality and Individual Differences, 16, 701–713.

-

Huebner, B., Dwyer, S., & Hauser, Grand. (2009). The role of emotion in moral psychology. Trends in Cerebral Sciences, 13, ane–half dozen. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2008.09.006

-

Hughes, Grand., & Cresswell, M. (1968). An introduction to modal logic. London, UK: Methuen.

-

Kalish, C. (1998). Reasons and causes: Children's agreement of conformity to social rules and physical laws. Child Evolution, 69, 706–720.

-

Kohlberg, L. (1981). Essays on moral development, Vol. I: The philosophy of moral development. San Francisco, CA: Harper & Row.

-

Komatsu, L. Thou., & Galotti, Chiliad. Thousand. (1986). Children'due south reasoning about social, concrete, and logical regularities. Child Development, 57, 413–420.

-

Kruglanski, A. W. (2004). The psychology of closed mindedness. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

-

Lombrozo, T. (2009). The part of moral commitments in moral judgment. Cerebral Science, 33, 273–286.

-

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1987). Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 81–90.

-

Moore, A. B., Clark, B. A., & Kane, M. J. (2008). Who shalt not kill? Individual differences in working memory capacity, executive control, and moral judgment. Psychological Science, nineteen, 549–557.

-

Morewedge, C. Chiliad., & Clear, M. Eastward. (2008). Anthropomorphic God concepts engender moral judgment. Social Knowledge, 26, 182–189.

-

Nichols, S. (2002). Norms with feeling: Towards a psychological business relationship of moral judgment. Knowledge, 84, 221–236.

-

Nichols, S. (2006). Imaginative blocks and impossibility: An essay in modal psychology. In S. Nichols (Ed.), The architecture of the imagination (pp. 237–255). Oxford, United kingdom: Oxford University Press.

-

Nichols, Southward., & Mallon, R. (2006). Moral dilemmas and moral rules. Cognition, 100, 530–542.

-

Paxton, J. M., Ungar, Fifty., & Greene, J. D. (2012). Reflection and reasoning in moral judgment. Cognitive Science, 36, 163–177.

-

Pellizzoni, South., Siegal, M., & Surian, 50. (2010). The contact principle and utilitarian moral judgments in young children. Developmental Scientific discipline, 13, 265–270.

-

Perkins, M. (1983). Modal expressions in English. London, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: Pinter.

-

Perkins, S. A., & Turiel, Due east. (2007). To prevarication or not to prevarication: To whom and under what circumstances. Child Development, 78, 609–621.

-

Pizzaro, D. A., & Bloom, P. (2003). The intelligence of the moral intuitions: Comment on Haidt (2001). Psychological Review, 110, 193–196.

-

Rottman, J., & Kelemen, D. (2012). Aliens behaving badly: Children'southward conquering of novel purity-based morals. Cognition, 124, 356–360.

-

Russell, P. S., & Giner-Sorolla, R. (2011). Moral anger is more flexible than moral cloy. Social Psychological and Personality Science, ii, 360–364.

-

Shtulman, A. (2009). The development of possibility judgment within and beyond domains. Cognitive Development, 24, 293–309.

-

Shtulman, A., & Carey, S. (2007). Improbable or impossible? How children reason about the possibility of boggling claims. Child Development, 78, 1015–1032.

-

Stephen, A. T., & Pham, M. T. (2008). On feelings every bit a heuristic for making offers in ultimatum negotiations. Psychological Science, 19, 1051–1058.

-

Strohminger, Due north., Lewis, R. L., & Meyer, D. E. (2011). Divergent effects of different positive emotions on moral judgment. Cognition, 119, 295–300.

-

Suter, R. S., & Hertwig, R. (2011). Time and moral judgment. Cognition, 119, 454–458.

-

Valdesolo, P., & DeSteno, D. (2006). Manipulations of emotional context shape moral judgment. Psychological Science, 17, 476–477.

-

Weisberg, D. Due south., & Sobel, D. Thousand. (2012). Young children discriminate improbable from impossible events in fiction. Cognitive Development, 27, ninety–98.

-

Wheatley, T., & Haidt, J. (2005). Hypnotic disgust makes moral judgments more severe. Psychological Science, 16, 780–784.

-

Woolley, J. D., & Ghossainy, M. E. (2013). Revisiting the fantasy–reality stardom: Children equally naïve skeptics. Child Development. doi:10.1111/cdev.12081

-

Zalla, T., Barlassina, L., Buon, M., & Leboyer, M. (2011). Moral judgment in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Cognition, 121, 115–126.

Writer note

We would like to thank Sarah Berkoff, William Krause, and Tori Leon for help with data drove and data assay.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shtulman, A., Tong, Fifty. Cognitive parallels between moral judgment and modal judgment. Psychon Balderdash Rev twenty, 1327–1335 (2013). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-013-0429-ix

-

Published:

-

Issue Appointment:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-013-0429-9

Keywords

- Judgment

- Decision making

- High-order knowledge

- Reaction time analysis

- Moral psychology

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/s13423-013-0429-9