according to hume, what is it rational to believe in miracles?

"Of Miracles" is the title of Department X of David Hume's An Enquiry concerning Human Understanding (1748).

Overview [edit]

Put simply, Hume argues non only that miracles violate the laws of nature,[1] merely that when a phenomenon is reported information technology is always more likely that the reporter is either malign or mistaken ("that this person should either deceive or be deceived"[2]) than that the phenomenon is true. For obvious reasons, the latter and highly provocative part of the statement has infuriated some Christians,[3] especially given the reference to the Resurrection in the following quote.

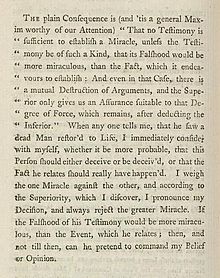

When anyone tells me, that he saw a dead man restored to life, I immediately consider with myself, whether information technology exist more likely, that this person should either deceive or be deceived, or that the fact, which he relates, should actually accept happened.... If the falsehood of his testimony would be more miraculous, than the issue which he relates; then, and not till then, can he pretend to command my belief or opinion.[4]

See the picture box below for the quote in its wider context.

Origins and text [edit]

Hume did non publish his views on miracles in his early on, 1739, Treatise, and the sections on miracles were frequently omitted in early on editions of his 1748 Enquiry.

For instance, in the 19th-century edition of Hume's Inquiry (in Sir John Lubbock's series, "One Hundred Books"), sections 10 and 11 were omitted, appearing in an Appendix with the misleading caption that they were normally left out of popular editions.[5] Although the two sections announced in the full text of the Enquiry in modern editions, affiliate X has also been published separately, both equally a split up book and in collections.

In his December 1737 letter to his friend and relative Henry Domicile, Lord Kames,[6] Hume set out his reasons for omitting the sections on miracles in the before Treatise. He described how he went well-nigh "castrating" the Treatise so as to "give every bit petty offence" to the religious as possible. He added that he had considered publishing the argument against miracles—also as other anti-theistic arguments—every bit part of the Treatise, but decided against it so as to not offend the religious sensibilities of readers.[seven]

The statement [edit]

Hume starts past telling the reader that he believes that he has "discovered an statement ... which, if merely, volition, with the wise and learned, exist an everlasting bank check to all kinds of superstitious mirage".[8]

Hume offset explains the principle of evidence: the simply way that nosotros can guess between two empirical claims is by weighing the testify. The degree to which we believe one claim over another is proportional to the degree past which the evidence for one outweighs the evidence for the other. The weight of evidence is a function of such factors equally the reliability, manner, and number of witnesses.

At present, a phenomenon is defined as "a transgression of a law of nature by a particular volition of the Deity, or by the interposition of some invisible agent."[9] Laws of nature, however, are established by "a firm and unalterable feel";[10] they rest upon the exceptionless testimony of countless people in different places and times.

Cypher is esteemed a miracle, if it ever happen in the common course of nature. It is no phenomenon that a human being, seemingly in good wellness, should die on a sudden: considering such a kind of death, though more unusual than any other, has yet been oftentimes observed to happen. But it is a miracle, that a dead man should come to life; considering that has never been observed in any age or country.[11]

As the evidence for a miracle is always limited, equally miracles are unmarried events, occurring at particular times and places, the prove for the miracle volition always be outweighed by the show against – the evidence for the law of which the miracle is supposed to exist a transgression.

There are, yet, 2 ways in which this argument might be neutralised. First, if the number of witnesses of the miracle exist greater than the number of witnesses of the functioning of the constabulary, and secondly, if a witness be 100% reliable (for then no amount of contrary testimony volition be enough to outweigh that person'south account). Hume therefore lays out, in the second office of department X, a number of reasons that we have for never belongings this condition to take been met. He first claims that no phenomenon has in fact had enough witnesses of sufficient honesty, intelligence, and instruction. He goes on to list the means in which homo beings lack consummate reliability:

- People are very prone to accept the unusual and incredible, which excite agreeable passions of surprise and wonder.

- Those with strong religious beliefs are ofttimes prepared to give evidence that they know is false, "with the best intentions in the world, for the sake of promoting and so holy a cause".[12]

- People are often too credulous when faced with such witnesses, whose credible honesty and eloquence (together with the psychological effects of the marvellous described earlier) may overcome normal scepticism.

- Miracle stories tend to take their origins in "ignorant and barbarous nations"[13] – either elsewhere in the globe or in a civilised nation's past. The history of every culture displays a pattern of evolution from a wealth of supernatural events – "[p]rodigies, omens, oracles, judgements"[14]– which steadily decreases over time, equally the culture grows in knowledge and understanding of the earth.

Hume ends with an argument that is relevant to what has gone before, but which introduces a new theme: the statement from miracles. He points out that many different religions have their own phenomenon stories. Given that at that place is no reason to accept some of them but non others (bated from a prejudice in favour of i religion), then nosotros must concur all religions to have been proved truthful – but given the fact that religions contradict each other, this cannot be the example.

Criticism [edit]

R. F. The netherlands has argued that Hume's definition of "phenomenon" need not exist accepted, and that an event need not violate a natural police force in order to be accounted miraculous.[fifteen] It has been argued past critics such as the Presbyterian minister George Campbell, that Hume'due south argument is round. That is, he rests his instance against belief in miracles upon the claim that laws of nature are supported by exceptionless testimony, only testimony tin can only be accounted exceptionless if we disbelieve the occurrence of miracles.[xvi] The philosopher John Earman has recently argued that Hume'southward argument is "largely unoriginal and importantly without merit where information technology is original",[17] citing Hume's lack of understanding of the probability calculus as a major source of mistake. J. P. Moreland and William Lane Craig agree with Earman's basic assessment and have critiqued Hume's statement against being able to identify miracles by stating that Hume's theory "fails to take into account all the probabilities involved" and "he incorrectly assumes that miracles are intrinsically highly improbable" [18]

C. S. Lewis, in his book Miracles: A Preliminary Study, argues that Hume begins by begging the question. He says that his initial proposition - that laws of nature cannot be cleaved - is effectively the aforementioned question as 'Do miracles occur?'.

Notes [edit]

- ^ Hume 1748/2000, 86-87

- ^ Hume 1748/2000, 89

- ^ For the nineteenth century controversy over Hume's argument, run across for instance Frederick Burwick, 'Coleridge and DeQuincey on Miracles', Christianity and Literature, Vol.39, No.4, 1980, pp.387ff.

- ^ Hume 1748/2000, 89

- ^ Antony Flew, introduction to Of Miracles, p. 3

- ^ E.C. Mossner, The Life of David Hume, p.58.

- ^ John P. Wright, "The Treatise: Composition, Reception, and Response" ch. 1 in The Blackwell Guide to Hume'south Treatise ed. Saul Traiger, 2006, ISBN 9781405115094, pp. 5–vi.

- ^ Hume 1975, An Research apropos Human Understanding X, i, 86

- ^ Hume 1975, X, i, 90n

- ^ Hume 1975, X, i, 90

- ^ Hume 1975, X, i, 90

- ^ Hume 1975, Ten, 2, 93

- ^ Hume 1975, X, ii, 94

- ^ Hume 1975, X, i, ninety

- ^ Holland, p. 43

- ^ George Campbell, A dissertation on miracles, pp. 31–32, London: T. Tegg, 1824 [i]

- ^ Earman, Hume's Abject Failure, Preface.

- ^ Moreland, J. P.; Craig, William Lane (2003). Philosophical Foundations for a Christian Worldview. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press Academic. pp. 569–lxx. ISBN0-830-82694-7.

References [edit]

- Burwick, Frederick. 'Coleridge and DeQuincey on Miracles', Christianity and Literature, Vol.39, No.4, 1980, pp.387ff..

- Campbell, George. A Dissertation on Miracles. 1762. Reissued New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1983. ISBN 0-8240-5403-2

- Earman, John. Hume'due south Abject Failure. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-19-512737-4

- Fogelin, Robert J.. A Defense of Hume on Miracles. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-691-11430-7

- Holland, R.F.. "The Miraculous". In American Philosophical Quarterly ii, 1965: pp. 43–51 (reprinted in Richard Swinburne below)

- Hume, David. Of Miracles (introduction by Antony Flew). La Salle, Illinois: Open Courtroom Classic, 1985. ISBN 0-912050-72-ane

- Hume, David. Enquiries concerning Human Agreement and concerning the Principles of Morals (introduction by 50.A. Selby-Bigge); third edition (revised and with notes past P.H. Nidditch). Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975. ISBN 0-19-824536-X

- Hume, David, 1748 et seq., An Enquiry Concerning Man Agreement, Tom L. Beauchamp (ed.), New York: Oxford University Printing, 2000.

- Johnson, D. (1999). Hume, Holism, and Miracles. Cornell University Press, Ithaca.

- East.C. Mossner, The Life of David Hume, Oxford, O.U.P., 1980.

- Swinburne, Richard [ed.] Miracles. London: Collier Macmillan Publishers, 1989. ISBN 0-02-418731-3 (contains "Of Miracles")

External links [edit]

- "Hume on Miracles" – function of the Stanford Encyclopedia article by Paul Russell and Anders Kraal

- "Of Miracles" – full text as part of the Leeds Electronic Texts Centre's on-line edition of the Enquiry concerning Man Understanding

- "Miracles" – dialogue by Peter J. Male monarch

- "Hume On Miracles" – commentary past Rev Dr Wally Shaw

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Of_Miracles